Benedicto Vox

From The Life of Benedicto Vox:

A Hagiography

1

The cursor on the terminal monitor rapidly blinked green. Light beamed through the stained glass of the small window on the upper wall, depicting a pastoral scene of a young shepherd watching over his flock. In the early morning, sunlight passed through the painted grass, washing the screen with an emerald glare. The aged monk seated at the desk squinted at the screen and reread the previous lines, unable to finish the manuscript.

His thoughts were muddled by the contradictions of documenting a faith that had evolved so much, yet so little, across the centuries. Each sentence he wrote felt like the hesitant prayer of a reluctant nonbeliever; each word a meditation on the infinite; each letter prolonged his destined resignation. He paused, his hand hovering over the key panel, a silent plea for divine inspiration. Outside, the morning choir of the distant city began to swell, a reminder of the world moving beyond the monastery's walls. Slowly, he returned his focus to the task at hand, feeling the weight of history pressing upon him, guiding his fingers to type the next word.

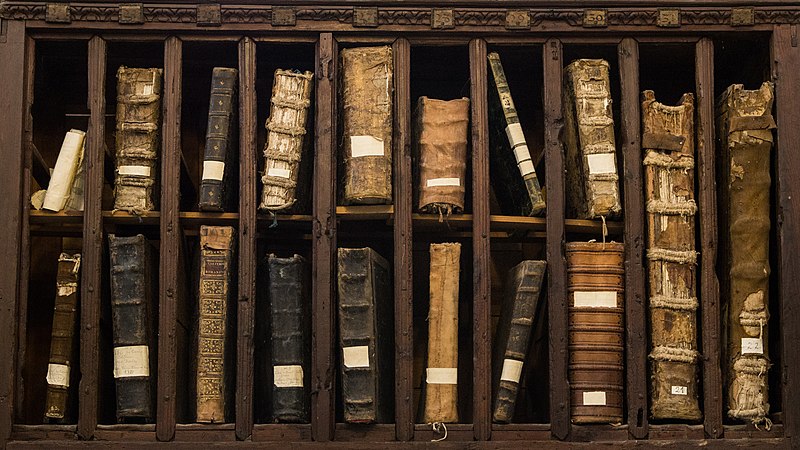

Benedicto Vox's monastic cell is a small, spartan[1] chamber steeped in the tranquil silence of Saint Selene Abbey's basement. The walls, made of rough-hewn stone, hold a coolness that contrasts with the warmth of the flickering terminal screen. Scattered about the room are simple wooden bookshelves burdened with books, scrolls, and various digital readers, which towered and leaned like the crumbling architecture of a forgotten kingdom. Several hand-carved wooden frames sit above his modest desk, where a terminal sits next to stacks of paper and writing tools, each enclosing a revered saint's picture. A narrow bed with a plain woolen blanket is tucked into one corner, and a small, arched window near the ceiling strains to pull in light, casting soft patterns on the stone floor. The room is austere yet imbued with a sense of purpose, mirroring Benedicto's life of simplistic yet focused dedication.

Benedicto Vox had not left his monastic cell in the basement of Saint Selene Abbey for several months. He wasn't an anchorite but was beginning to feel like one. His skin had grown pale. His hair (what was left of it) had grown long, white, and unruly. It matched his robe (when freshly cleaned, which had been several days ago). His beard had started to resemble the saints he admired and modeled his own life after, whose pictures were in simple wooden frames propped along the walls where the stone protruded unevenly from the surrounding masonwork.

Meals, books, writing supplies, and other items were left at his door while he worked. He never saw who brought them. He would simply leave a list outside, and then someone would knock and leave the requested items at his doorstep. The speed depended on the complexity of his request. Tea and coffee could be brought in a few hours. Book requests usually took a day or more unless they could be delivered as a digital codex. He recently requested the original written notes of Saint Barlowe's study of the Eridani solstice, and to his surprise, a library clerk brought them to his room in a matter of weeks. However, it was a lousy facsimile, not the original. The original journal and the early copies were likely only preserved in the Ecclesiastical library on Eridan, which Barlowe had founded.

As the days bled into one another, Benedicto became increasingly detached from the cadence of life outside his solitary cell. He once led evening vespers, but his studies now consumed his every waking moment. He had been given the Church's blessing to let his research carry him wherever it led, but his world narrowed to the flickering light of the terminal, the ancient texts, and the endless loop of research and writing. Despite the isolation, there was a comfort in the routine, a harmony between his ascetic lifestyle and the monumental task he had undertaken. However, the recent arrival of the facsimile of Saint Barlowe's notes stirred something within him. It was not just the thrill of holding a piece of history—albeit replicated—but a reminder of the vastness of the universe and the church's role within it. This realization rekindled a curiosity about the current state of the world beyond his monastic confines. His fingers paused over the key panel, contemplating the scope of his manuscript.

The Church had commissioned Benedicto Vox to gather contemporary texts and develop an updated, revised history of the fifth-millennium Church. He was the foremost scholar and expert on Eridani studies, mainly because of his connection with the original missionaries. Benedicto was fortunate to have met Saint Selene as a child before she left for Eridan in the 4370s. He had been one of the biggest advocates for Saint Selene's canonization after death, which is thought to have been around 4391, but because of the disappearance of the SCRIBES[2]., the exact date is uncertain. Many early documents from the fourth millennium have been well preserved, such as the first Interplanetary Council of 3298 and the anonymous writings by church scholars known collectively as simply The Historians. However, the fifth millennium was less documented because of the 41st-century schism and the disappearance of the SCRIBES in the 45th century.

Benedicto had requested a copy of the most recently published ecclesiastical history, a large codex known informally as The Quarternary. He had not expected someone to return so quickly. He jumped at the sound of the customary knock. He had returned to his writing and was deep in thought when interrupted by the knock, which sounded heavier and more urgent than usual.

The knocking continued until he reached the door. When he opened the creaking wooden door, he was—unusually—met by Prior Wells standing in his doorway. Usually, his supplies were placed by the door, and the person delivering them was gone by the time by the time he opened the door.

He had only met Prior Wells on rare occasions in passing or at meals, but since his increased commitment to his work, Benedicto had ceased attending common meals. Benedicto assumed Wells had to be far too busy to go on a supply run. So, why had he delivered the book personally?

“Good morning, Brother Vox. I hope your work is going well. Here is the book you requested. I think you'll find Appendix C most helpful for your work on the final days of Saint Selene. I know that is the period giving you the most difficulty.”

Benedicto took the large book from the Prior and thanked Wells for retrieving it. Before he could ask for more information, Wells turned away and left.

Confused by what had just happened and unsure what he expected to find, Benedicto wasted little time turning to the third appendix of The Quarternary. A small note fell from the pages, carried slowly to the ground by the breeze coming through the still-opened door. Written on the paper in barely legible handwriting were the letters SCRIB with an address underneath. The note had been folded and unfolded so many times that the E and a portion of the address had torn away—likely a long time ago since he couldn't imagine who else other than him would have requested this book in recent years.

Perhaps, he thought, it is time to venture out.

***

Footnotes

[1] This term refers to an ancient civilization Benedicto mentions in his notes which were discovered after his death. It is unclear from which texts he had discovered the term. Despite numerous attempts noone has been able to ascertain more details about this lost people. ↩

[2] Synthetic Clerical Record and Information Broadcast Entities ↩