From Travels of Lina the Pilgrim [1]

As recovered from the Eridani Archive, 4476

Fifth Common Edition prepared from the Vox Fragments

Scribal Note on the Present Text

The account known as Travels of Lina the Pilgrim was found among the so-called Vox Fragments, recovered in 4476 from beneath the collapsed western annex of Saint Selene Abbey. The fragments included water-damaged notebooks, encrypted hardrives, and fragmented memory chips, many of which bore no obvious indexing. Within these, preserved in both longhand script and transcribed digital entries, was a continuous narrative written in the voice of one calling herself Lina.

Though traditionally attributed to Benedicto Vox, who labored in the Abbey's archives during the mid-Fifth Millenium, the present form of the text appears to postdate his life. Internal inconsistencies suggest that Vox may have begun the recovery or annotation of the documents but did not complete the work. The question of who compiled or edited the final version remains unresolved.

The journey described herein takes place in the year 4400. It records the pilgrimage of a woman who, despite institutional disinterest and the passage of time, resolved to travel to Eridan in search of Saint Selene. Her narrative is interwoven with devotional meditations, fragments of verse, and visionary accounts of uncertain origin.

For the sake of readability, minor orthographic errors have been normalized, and some corrupted sequences reconstructed with minimal conjecture. Original markings have been retained where meaningful. The voice is believed to be authentic.

Chapter One: The Calling and the Silence

“Before the journey begins, there is a stirring. It does not speak. It does not explain. It only draws.”

—Revelations of a Scribal Faith, Selene Clarya

I do not remember the moment I first loved her—only the quiet accumulation of reverence. A phrase here, a marginal note there. The way her absence pressed itself into the footnotes of history. It was not lightning, but sediment. Not vision, but ache. Her name became something I carried before I ever thought to follow it.

If longing is a kind of vow, then I was consecrated long before I chose to leave.

1

Most assumed that Selene died sometime during the late 44th century. The most common date cited is 4391—shortly after her last writing arrived at Earth. Her final recognized work, Revelations of a Scribal Faith, offers an account of her early life and her decision to enter the anchorite path. It also summarizes her decades of life on Eridan, her collaboration with the SCRIBES who tended the monastery, and provides rare insight into the religious culture, perspectives, and practices that had taken shape on Eridan over the previous centuries.

I was born in the middle of the 44th century, the summer of Earth year 4365—when the memory of Saint Selene had already crystallized into legend, and the Church's maps showed Eridan only as a footnote—“inhabited once.” I had read every word ever committed to record about her: the sermons, the fragmentary letters, even the forbidden accounts whispered among certain Sisters of the Outer Orders. Some claimed she died there, her bones mingled with dust beneath the blue-lit cliffs. Others said she simply vanished. A few insisted she had never truly lived at all, only appeared when needed, as grace sometimes does.

But I believed differently. Not out of blind devotion—though I was not without devotion—but because in the long nights of my novitiate, I heard the silence of Eridan calling to me. Not absence. Not echo. A silence that was full, like breath held before speech.

And so I began to prepare.

I told no one. I sought no blessing.

There were protocols, of course—years of preparation, screenings, authorizations, and theological approvals required for any ecclesiastical venture beyond orbit. I followed none of them.

Instead, I went to the archive at Mare Acidalium and requested access to the Transit Records. Most had been sealed, but a scribe named Mareda—one who had once copied The Minor Testimonies of Eridan by hand—took pity on me. She allowed me to view the service schedules and shipping manifests for the outer sectors. From that, I learned the name of a freight vessel contracted to deliver survey drones and dry equipment to the Eridani surface. I memorized the dock schedule. I found a way in.

I brought little: three veils, one for warmth, one for prayer, and one I could afford to lose. The small reliquary that had belonged to my grandmother. A wafer of dried bread from the Chapel of First Orbit. And a copy—imperfect and fragile—of the Eridani Canticles, handwritten in my own ink.

In the ninth year since her presumed death, in the year 4400 by Martian reckoning, I departed.

2

In 4347, the then Sister Selene Clarya made her first journey to the monastery on Eridan. She returned again in 4379 to dwell there as an anchorite. I, too, was born and raised near her birth city of Terten, and from an early age I was steeped in the reverence her name carried—her writings, her silence, and her singular devotion. Her life was not only remembered, it was studied.

So, as soon as I was of age, I left home and entered an abbey, driven by the hope that I might become a scholar of Selene and of the early figures of the Eridani Church. I believed that through study—through proximity to memory—I might come to understand what she had found, or perhaps what she had left behind.

I spent those early years copying manuscripts, annotating fragments, and tracing disputed dates across brittle chronologies. My devotion was not marked by ecstatic visions or outward acts of piety, but by patient labor—by ink, by silence, by small hours spent transcribing texts others had long since abandoned. I translated variant readings of her letters. I mapped conflicting itineraries from her final decade. I gathered disputed quotations and placed them side by side, not to resolve them, but to dwell in their tension.

Selene was not yet a saint, but among certain circles—quiet ones—she was already holy. The formal Church had not yet spoken, but in cloisters and scriptoria, her name was whispered alongside the names of desert mothers, martyrs, and mystics. I never presumed to speak for her legacy, only to follow its echoes through the written word.

It was during these years of study that the question of her canonization, once improbable, began to shift into likelihood.

3

Given her presumed death, she became a candidate for canonization. As a Servant of God, all of her writings were gathered and scrutinized. This became an especially active period for me—both as a recognized scholar and as a devotee of Selene and her legacy. The process from Veneration to Beatification moved with remarkable speed, and culminated in 4399 with her canonization by Pope Victor IV.[2] It was one of the fastest canonizations in Church history.

Strangely, after her elevation to sainthood, both her advocates and her critics seemed to vanish from public discourse, retreating quietly into private study. Despite the reverence she had commanded in life, few continued to engage her writings deeply in the years that followed her canonization.

At one time, the Church regarded Selene’s work on Eridan as among the most significant developments in sacred scholarship since Saint Barlowe’s Easter calculation, the founding of the Eridani library, and the early field studies—most famously, the documentation of the calcifying fungi once used in monastery construction.

But the demand for my translation and editorial work diminished after Selene's actual final manuscript was recovered and dismissed. That final work—unlike the polishedRevelations of a Scribal Faith—was deemed unintelligible: a chaotic compilation of unsolved equations, hand-drawn diagrams, and obscure verses that read as nonsense. The official consensus was clear: these were the last, disordered thoughts of a woman unravelled by isolation, hunger, and the extremities of ascetic devotion.

Whether Selene was dead or still alive, I could not say. But I refused to let that text be the end of her story. Though I may have stood alone in this belief, I was certain of one thing:

She might still be alive on Eridan.

Chapter Two: The Hidden Transit

“You do not find the threshold. You pass through it when no one is looking.”

—The Anchorite’s Table, Fragment 12

I have come to believe that holiness rarely arrives with certainty. It slips in through cracks in the schedule, into moments unplanned—between inspections, beneath announcements, behind silence. The first steps of a true pilgrimage are almost always missteps.

I did not board in courage, but in quiet. I did not speak a vow aloud. I passed no test. But still I went. And if I was wrong—if I misunderstood the call—then let this be remembered: that I moved anyway. That I entered the dark.

1

In 4400, the Vatican announced its final mission to Eridan—the distant monastery once known for the most extensive use of SCRIBES of any galactic diocese. My heart pounded with excitement and fear as the ship's final checks were underway. I had studied the ship’s layout for months and knew the service vents and maintenance halls like the back of my hand—a necessity if I wished to remain undetected.

With the cargo-bay crew focused on their pre-launch routines, I slipped into a narrow access panel behind the loading station. The machine crew was fully absorbed in their programmed tasks, and the human officer stood by silently, only present in case of technical failure. They would not pose a threat—not if I moved swiftly.

***

In truth, I snuck aboard.

***

I had rehearsed the motion a thousand times in my mind—every grip, every step, every breath held between turns of the head. But nothing prepares the body for its own trembling. I moved swiftly, but not without fear.

Once inside, I did not pause. Hesitation is a luxury for the authorized, not the hidden. I crawled through a narrow shaft just beneath the secondary intake vents and descended into the maintenance corridor. There, I waited—not to catch my breath, but to listen. The machines were humming in place. The silence of the humans was a different kind of sound.

My veil had slipped. My palms were scraped. The taste of metal lingered on my tongue. But I was in.

That was how it began—not with revelation or triumph, but with ductwork and darkness and my heart drumming in my ears.

2

So, in the year 4400, I boarded the STS[3] Zenith Sanctus, the final ship planned for travel to what remained of the Eridani monastery—an outpost that had gone by many names across the centuries. It was first founded by Saint Argus, and later sustained by generations of scholars and their attending SCRIBES. Over time, nearly all the roles once held by human hands—liturgist, archivist, herbalist, even confessor—had passed into the care of SCRIBES.

But their presence, once central, had long since faded. The use of SCRIBES across the Interplanetary Church began to decline after the Schism of 4027 and vanished almost entirely following Selene’s presumed death. Scholar Idris Cora argued that this was no coincidence. In her final, unreadable notes—composed of equations, diagrams, and marginal symbols—Selene may have altered something fundamental in the SCRIBES themselves. Or perhaps something had happened on Eridan that transformed them in ways we could no longer recognize.

I did not understand what Cora meant by “transformed beyond measure.” I only knew that the monastery had once been alive with memory and movement—and now, it was still.

3

The ship’s stated purpose was to survey the planet for any remaining SCRIBES or signs of residual activity and to retrieve any important volumes from Barlowe’s library that had not yet been copied or preserved. The Zenith Sanctus was not intended for human passengers.

However, interplanetary regulations still required the presence of at least one trained human crew member. This was a precaution—an institutional scar left by the Oracle ship disasters of the late 3900s, when returning vessels from deep-veneration pilgrimages suffered catastrophic failures. The AI systems had encountered unanticipated navigational anomalies, and without human oversight, entire cargoes—and many lives—were lost.

Since the manufacture of so-called “true” SCRIBES had been outlawed, the Zenith Sanctus was outfitted only with low-grade systems—machines said to resemble the mundane survey equipment once used by the ancients to test extraterrestrial soils, long before the age of meaningful interplanetary travel.

But I did not believe the claim.

These were not simple instruments of geology or navigation. I watched them when they passed, stiff-legged and silent, scanning corridors and recalibrating themselves in response to movement I hadn't made. I suspect they were security machines, retrofitted for mission compliance. Whatever their stated function, they moved with purpose—and that purpose felt more watchful than servile.

4

I boarded in darkness. The docking bay at Mare Acidalium was operating under night-cycle protocols, and the crew had already sealed the main corridor. But the subdeck remained partially exposed—open just long enough to receive the last shipments of tethered cargo. That was my window.

I moved like a technician on late inspection: plain robe, data-slate in hand, veil pulled forward to blur my face. No one looked twice. I passed the cargo sensors, ducked behind a loading scaffold, and slipped through the maintenance hatch while the platform's machinery groaned and realigned.

Inside was colder than I had expected—colder, even, than the outer air. My breath caught and hovered. I followed a narrow passage that wound behind one of the central coolant conduits and found a place just large enough to crouch in. It was a hollow between panels, part of a defunct filtration system. I had memorized it from an old ship schematic—decommissioned, yes, but never properly redacted from public archives.

I moved quietly and calculatedly. The interior was cramped, lined with cables and pipes, and dimly lit by the occasional flicker of emergency lights. I crawled forward, the metal cool against my skin, trying to avoid making a sound. I found my way to the small, seldom-used storage room I had identified earlier in the schematics as my hideout for the trip. Surrounded by spare parts and maintenance tools, I settled in, pulling my knees close to my chest.

Although the ship was primarily uncrewed, if my suspicions were correct, the computers and machines onboard had the most advanced security tech known at the time. They could detect changes in temperature and even the faint sound of breathing—and heartbeats. Although many rejected calling them SCRIBES, to me, these units seemed exactly that. Not the kind I had read about—those programmed for liturgy, academics, or scientific inquiry—but something else. SCRIBES retooled for silence and surveillance. SCRIBES prepared, if necessary, to kill.

Outside my confined hiding spot, the hum of the ship grew steadier, a sign that the engines were coming to life. I felt a slight shudder run through the structure as the ship disengaged from the dock. My breath caught—the adventure (or something like it) was beginning. Sure, I was stowing away to see the stars, but my mission was personal—spiritual. I needed to find out what had happened to the SCRIBES and, if possible, to secure the legacy of Selene, the Last Anchorite of Eridan, which held secrets no delivered digital copy could preserve.

***

Author's Note:

It is unclear how Lina met her basic needs, like food, water, and hygiene, on the long journey. The trip took several months to a year, depending on the ship's speed. The ship was likely traveling faster than usual under the assumption that no humans were onboard.[4] Records suggest that she may have carried a travel suit capable of storing small quantities of high-calorie food and water, with a built-in waste system. All ships of the era included waste disposal and no-rinse hygiene kits, though she would not have had access to anything resembling a proper shower until arrival. These speculations are based on extrapolation from known technologies of the period, as Lina herself offers no comment on the practical aspects of the journey in her writings

***

There I stayed.

The launch came several hours later, unannounced. The tremor was sudden and profound. Not a roaring, as I had imagined, but a deep bodily shift—as if the bones inside me had been nudged out of their earthly contract. I did not pray. I listened.

Somewhere above me, engines bloomed.

5

Days passed. I kept to my hollow, emerging only when the corridors dimmed for night-cycle and the machines returned to their docks. I rationed my bread with care and drank from the condensation coils near the auxiliary vents. I learned the rhythm of the vessel—the pulse of its systems, the hesitation before a course correction, the subtle difference between movement and surveillance.

Once, I heard footsteps.

They were human, or close enough. Lighter than the tread of the machines. Slow. Deliberate. I held my breath as they passed, then faded.

I told myself it was a memory—the echo of a technician from some earlier departure—but a part of me knew better. The protocols required one crew member, and now I had felt the truth of that presence, faint and distant.

I did not yet know who it was.

And I was not ready to be seen.

6

There is a particular kind of stillness that descends after fear has passed but before trust begins. I lay curled in my hiding place, the chill of the walls pressing through my robe, and tried to convince myself that the footsteps had been a dream—a phantom echo summoned by nerves and recycled air.

But I could not shake the feeling that I was not the only one listening. That someone—or something—else aboard the Zenith Sanctus had noticed the subtle ripple of my presence and was waiting, just beyond reach. Not to confront. Not yet. Only to observe.

I counted my breaths. I whispered no prayers, only fragments of old canticles I barely remembered. Silence became my liturgy. Vigilance, my only vow.

Chapter Three: The Vision in Transit

“The saints travel farther than our prayers know how to follow.”

—Epistle to the Void-Posted Sisters, 2:19

Even when the body is still, the soul sometimes slips its orbit. I have found that visions do not announce themselves. They arrive like hunger—gradual, then unbearable. I did not seek revelation, only silence. But something found me in the silence.

1

Roughly midway through the trip, the ship went dark.

The machines had powered down, entering a low-energy state. This stretch of transit required minimal navigation, and the automated systems likely deemed the silence more efficient than motion. Security routines grew intermittent, their intervals widening. No lights pulsed in the hallways. No voices murmured from consoles. Even the steady thrum of propulsion had faded into a low, distant hum—barely distinguishable from the vessel's own metal breathing.

There was no way to measure the passage of time. We had not yet reached the year mark, but the days—if they could still be called that—had become indistinguishable. I occupied myself with prayer and contemplation, and with reading the few hand-bound volumes I had carried in my travel pack. I had chosen not to bring digital texts; electricity could not be trusted, not by a stowaway. Paper was slower and less efficient, but it remembered how to survive the dark.

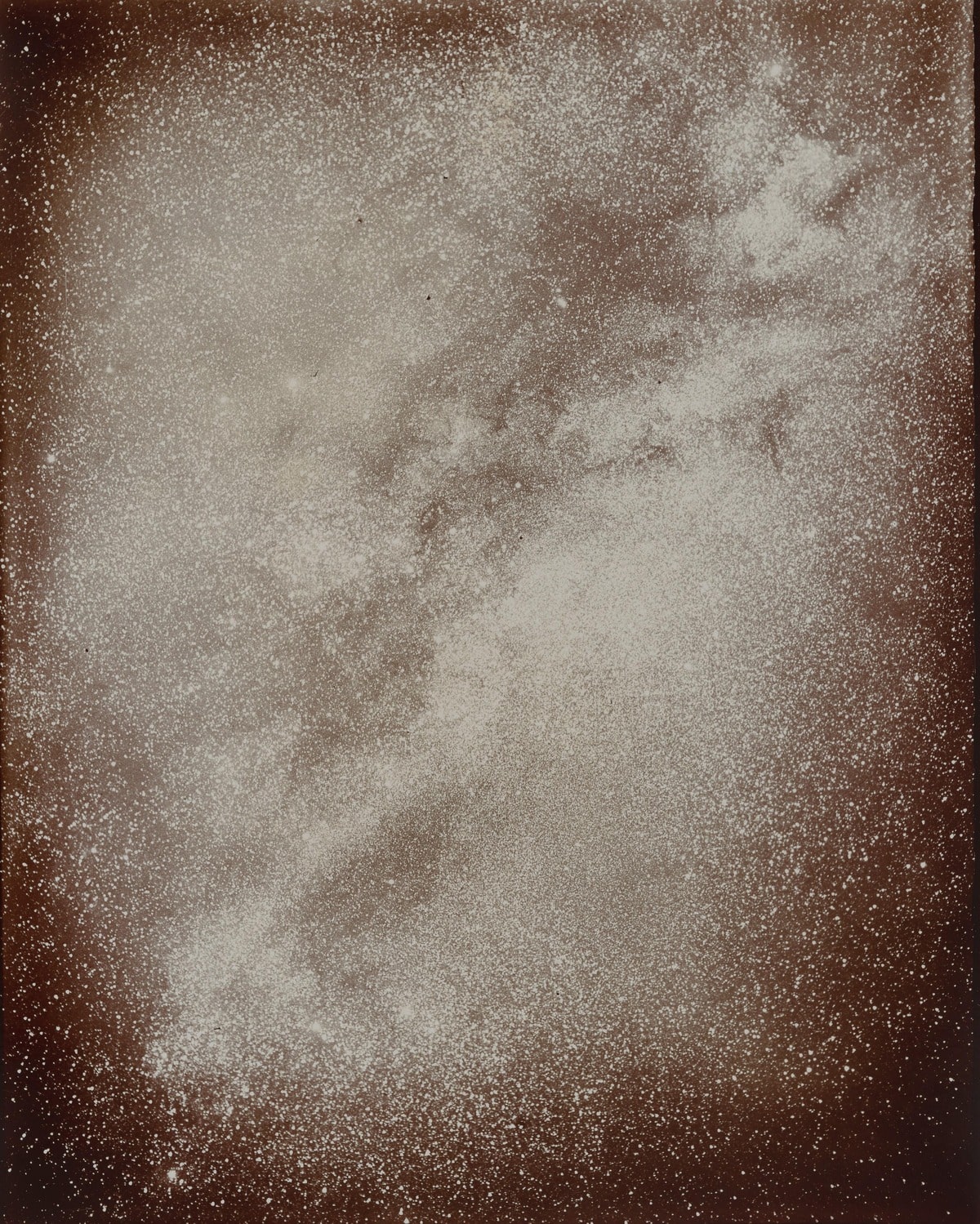

Confident that I had gone undetected thus far, I ventured into the central corridor during one of the ship’s low-power cycles. I moved slowly, listening for the hum of reactivating systems, but all remained still. Along the walls were a few narrow square windows—darkened by dust and rimmed in frost—with a view of deep space.

We were far beyond the outer planets, well outside the familiar corridors of the local solar system. No stars were close enough to name. No landmarks offered orientation. There was only the vast and unreadable dark, pierced occasionally by light that felt older than thought.

I moved cautiously, placing each step with care to muffle its sound. The corridor was dim, lit only by the soft blue glow of dormant control panels and the flicker of the occasional overhead diode. Nothing stirred. The crew was nowhere in sight.

My eyes were drawn to the forward windows in the main cabin—once designed for human pilots, but now largely obsolete. Based on everything I had seen these past months, it seemed increasingly likely that I was, in fact, the only human aboard.

I couldn’t resist pausing to look out.

The darkness of space was total, broken only by the scattered glint of distant stars—so faint, so far, they seemed more imagined than real. And yet, they were real. Infinitely far, and still visible. The limitations of modern spaceflight meant we would never reach them—not in this generation, and not in the next. Still, they watched us as they always had.

I pressed my face against the cool glass. The chill grounded me. Out here, the concerns of one stowaway—her hunger, her fear, her questions—felt almost comically small. But in that smallness, I felt a strange joy. I was alone, surrounded by the unknown, and carrying a secret that no one else had chosen to carry.

But then—something moved.

It wasn't a star, and it wasn't a machine. It had no trajectory, no mechanical rhythm. It simply was, suspended in the void just ahead of the ship, where there should have been only darkness. For a long moment, I couldn't tell if I was seeing with my eyes or with something deeper.

Breaking up the expansive void, a (relatively) short distance ahead of the ship, I could see something colorful. It would not be exactly accurate to call it shapeless, but that is the closest word I can think of to describe its dimensions. Still, I could not truly describe its shape—it lacked discernible boundaries, yet was undeniably there. It was growing and receding at once, pulsing with a precise rhythm—like a very slow heartbeat.

Its color was unlike anything found on Earth. I want to say it resembled a soap bubble, or a puddle of oil on asphalt after a heavy rain—but neither image does it justice. It shimmered and rippled like a fluid, like light seen through water, but that didn't make sense. Nothing out there should shimmer. And nothing should breathe.

As I stared, transfixed, the shifting mass began to swirl with slow, deliberate motion. The colors folded into each other like auroras—but not like any aurora I had ever seen on Earth. These were infinitely more complex, layered with patterns that twisted into and out of dimensions I had no names for. It was as though this entity—or phenomenon—possessed a luminosity beyond the human spectrum, or perhaps it danced along the edge of it, slipping just beyond perception even as it revealed itself.

Each pulse ushered in a new wave of color, some of which I could not describe, and a few I suspect no language has ever captured. These were not colors meant to be recorded. They existed only in that flickering instant before transforming into something else entirely—fleeting, unknowable, and yet utterly real.

And it was not just visual. I felt it. Not in my body, but in that unspoken part of the self where fear and awe converge. Wonder rose within me—true wonder—and with it, a quiet, aching trepidation. What was I seeing? A natural cosmic anomaly? An alien life form? A vestige of something older than both?

Or was it, impossibly, Selene?

Maybe it was only the solitude speaking. I had spent so long in silence, in darkness, that even a trick of the eye could feel like revelation. But this didn't feel like a trick. It felt like a summons.

And I could not record it. I had no camera, no instruments—only memory, and a dwindling sense of time. Whatever this was, I would have to carry it in me, and recall it—if I could—many months from now, on a world I had not yet reached.

Still, the mystery beckoned. The ship drifted forward. And I felt something watching.

As the ship drifted closer to the shimmering anomaly, I began to feel… strange.

A warmth spread through me—not external, but internal, as though something within had been set aglow. The sensation intensified with each passing moment, growing steadily warmer the nearer we drew to the colorful presence. Was it an orb? A veil? A threshold?

I did not know what would happen if—when—we passed through it. My breath quickened. My hands trembled. I leaned closer to the window, drawn as if by gravity, desperate to see just a little more.

And then my elbow bumped a control panel.

The sound was immediate and piercing: a high-pitched sequence of beeps that echoed through the corridor like an alarm in a cathedral. Lights blinked. Somewhere deep in the ship's belly, systems activated.

The silence was over.

heard them first—the machines—whirring into motion, their heavy limbs clicking against metal grates as they approached. Their footsteps, if they could be called that, were deliberate and inhuman. Closer. Louder.

Then I saw them. Their frames emerged from the shadows at the far end of the corridor, glowing with cold diagnostic light.

My breath caught. My limbs refused to move.

This was it.

My pilgrimage was about to end—not in revelation, but in detention. Maybe even worse.

I backed away from the window, heart pounding, unsure whether to run or hide—unsure if either would matter. The corridor seemed longer now, the light colder. The machines advanced without hesitation, their joints hissing softly, scanning every surface with sweeping beams of pale blue light.

I ducked behind a storage panel, pressing myself into the shallow recess, barely breathing. My mind raced through every contingency I had imagined—none of which had prepared me for this. Would they alert the crew? Confine me? Eject me into space?

Or worse—what if they didn’t respond like machines at all?

Footsteps. Real footsteps now—slow, measured, unmistakably human. The whir of machinery fell still.

Someone was with them.

2

Just when I thought I would be seized—just when I prepared to abandon any hope of escape—a new light appeared.

It came not from the machines or from any corridor panel, but from the very air. The moment the ship breached the edge of the anomaly, something changed. The structure vibrated—subtly at first, like a harmonic overtone trembling through the bones of the vessel. Then light began to seep through the seams of the ceiling, then the walls, as if the hull itself had turned translucent and was now filtering some celestial radiance from outside. The machines froze mid-step. Their optical sensors dimmed. The corridor fell into an unnatural hush.

Upon entering the colorful shape, a light emerged within the ship. At first, I panicked—sure that it would draw even more attention, trigger an alarm, summon every system still active. But the light did not trigger anything. Instead, it took form.

Slowly, deliberately, the light coalesced into the shape of a woman.

At first she was only an outline—glowing edges, a soft curve of shoulder and cheek. But with each passing moment, her features sharpened. Her face became clear. She was smiling, and her eyes met mine with unmistakable calm.

“Lina,” she said. “Do not be afraid.”

The machines, which had been closing in with mechanical certainty, halted. Their limbs froze in place. Their eyes—those dull, glowing sensors—dimmed to black. It was as if her presence had unraveled their purpose.

Had she… stopped them?

The light surrounding her softened. Her face remained aglow, and her hair flowed through a shifting spectrum of color—red to silver to white, and back again. She did not appear to age before my eyes—she appeared to be age itself: youth and wisdom, fire and frost. She was radiant and ancient, full of gentleness and terrible power. She was the strong Rhiannon and the wise Witte Wieven. And she was someone I thought I knew.

I could not move. I could hardly breathe. I could not gather the courage or power to move or to respond.

“Do not be afraid,” she repeated.

“Who are you?” I whispered, not even sure the sound had left my lips.

“I am who you seek. Do not despair. You will arrive soon. Do not forsake your mission. You trusted that my parting words were important.”

“Selene?” I said. “I don't understand. I didn't understand what you wrote.”

“You will soon enough.”

“What were you trying to tell us?”

“Not me,” she said, “but we. There is another also. Seek the final anchorite's guidance.”

I cannot record the final words she spoke. Let it be enough to say that they are for me alone. To share them would risk reducing them. When I reach Eridan, I will seek their meaning—if, indeed, it was Selene who appeared to me. Or if she was something else entirely.

Then the light around her began to swirl. The necklace she wore—silver, delicate, hung low—began to glow with a quiet blue intensity. It brightened, spinning outward into a spiral of starlight—like a galaxy opening inside her chest.

And then, without a word, she was gone.

The ship was dark again.

The machines remained motionless. Their senses had not yet returned. This was my chance—to move, to disappear, to reach the ship's archive room before anyone or anything remembered I was there.

3

I stayed frozen in place long after the light had vanished.

What had just happened? A vision? A memory? A visitation? I had no words for it—only the echo of her voice in my chest, and the strange calm that followed it. It did not feel like clarity. It felt like being unmoored. As if something vast had brushed against my mind and left it trembling.

I could still see her necklace—the spiral of light, the impossible blue.

I had spent years studying Selene's words, chasing her silence across forgotten pages. I thought I had known what I was searching for.

But now I was no longer sure.

I thought I heard footsteps again—soft, too human to be one of the drones. Shaking off the last threads of reverie, I turned and moved down the corridor toward the archival chamber, away from the sound and toward what I hoped was just one of the uninvolved crew members on a maintenance loop.

If there were any records worth finding—logs of the SCRIBES, fragments of the Eridani manuscripts, or even marginalia from previous pilgrimages—they would be stored there. I quickened my pace, each step sharpening my senses. Any corner could reveal a security unit or a crew member who wouldn't be so easily stunned by light.

What the hand touches, the soul readies.

No one agrees. But in this moment,

it is both vessel and vow.

As I walked, I brushed my fingers against the small memory chip tucked in my pocket[5]—a fragile wafer of encoded purpose. Its presence steadied me. It reminded me why I had come. Why I had risked everything—

"do not forsake your mission."

4

Reaching the door, I paused and listened. Nothing. No footsteps, no voices, no mechanical hum.

I pressed the access button. The door responded with a soft click and slid open with a quiet whir.

I pressed the access button. The door responded with a soft click and slid open with a quiet whir.

The room beyond was dim and reverent. Rows of digital archives lined the interior, interspersed with sealed cases of ancient texts[6], each preserved behind glass filled with a foul-smelling inert gas—recently developed to prevent the decay of delicate materials, and still imperfect. The air was sterile, artificial, but heavy with implication.

I stepped inside. My heart pounded in my throat.

The room was neither vast nor ornate, but it radiated presence. Centuries of knowledge slumbered around me—encrypted, entombed, waiting. For a brief moment, I felt inviolable. The fear of the corridor, the trembling of the vision—all of it quieted here.

Here, in the silence, I felt reinvigorated.

Here, in the silence, I felt reinvigorated.

It was time to uncover what had been hidden.

They say the saints dwell in light, but I have always found them in stillness.

This room was not hallowed by incense or hymn, but by silence and breath held too long. I stood surrounded by texts no one had touched in generations. Some of them may never have been read at all. How many prayers had been whispered over their creation? How many truths sealed away, waiting not for a scholar—but a pilgrim?

Some are hidden so they can ripen in silence.

There is a holiness in things forgotten. I believe that now.

We carry so many questions into the dark. But sometimes the dark carries something back to us.

4

“You aren’t supposed to be here.”

I froze. My breath stopped. The voice was calm—neither angry nor alarmed—but unmistakably directed at me.

“You aren’t supposed to be here,” the voice repeated, this time with a question woven in. “Are you?”

The second version was softer, though still rhetorical. It wasn’t really a question of access or authorization. It was a statement of fact, spoken by someone who had clearly caught me—despite all my caution—red-handed, trespassing in a place where I did not belong.

There was nothing I could do.

I was a stowaway aboard a ship far from Earth, farther still from any habitable planet or populated station. There was nowhere to run. Nowhere to hide. After what felt like an eternity, I turned toward the voice.

The archive room was dim, but the glow from the control terminals lit the outline of a figure—an older man, standing in the doorway. His face, at first set in a mask of stoic reprimand, began to shift. His expression softened. A slow, almost amused smile crept across his mouth.

“I asked you a question,” he said, now stepping forward, making direct eye contact.

I didn’t answer. I wasn’t afraid—not of him, at least—but I still hadn’t found the words. What could I possibly say? I had broken into the ship’s archive. I was never supposed to be here. I wasn’t even supposed to exist aboard this vessel.

“You must be starving,” he said, still smiling. “Hiding out for this long—even if you packed provisions, it couldn’t have been much. Come on. You can’t eat in here, obviously.”

I wasn’t sure if this was a trap—some ruse to lure me away from the archive so I could be detained. I had surely violated more than one Interplanetary Transit law, and ecclesiastical infractions as well. But what choice did I have?

I couldn’t go back to my original plan—to investigate and recover SCRIBAL materials or Church records. Not now. And I certainly couldn’t run. What would that even accomplish? Yes, the ship was large, but not that large. Not large enough to outrun pursuit.

So I followed him.

I kept a careful distance as he led the way, unsure of his intentions. He seemed harmless enough. And to be honest, I was starving. But something still made me hesitate. There was something odd about his eyes. I couldn’t see clearly in the archive’s low light—just a flicker of something I couldn’t name.

“I am Brother Wells,” he said as we stepped back into the corridor. “Matthias Wells.”

“I’m Lina,” I replied, finally breaking the long, uneasy silence that had stretched between us.

“And what brings you aboard, Lina?” he asked, without turning.

“I’m on a pilgrimage,” I said—careful, measured. I offered nothing more than I had to.

I did not tell him the whole truth.

Not out of malice, but survival.

until the silence was friendly.

Some lies are thin veils worn until the air is safe to breathe.

And yet even now, I wonder if a pilgrimage concealed is still a pilgrimage confessed.

There is something sacred in being caught—not in punishment, but in the moment after, when the one who finds you chooses not to turn you in, but to welcome you instead.

I have studied the lives of saints and anchorites, read about their trials in desert and dark. But no one ever wrote about the hunger. Or the fear of a stranger’s kindness.

I followed him not because I trusted him.

I followed him because he offered me something I no longer knew how to ask for: food, and a place to be.

“That is admirable,” he said. “Pilgrimages have always been an important part of the Church’s history. And what is it you hope to gain from this pilgrimage?”

“To seek the anchorite of Eridan—or to seek her guidance, I mean.”

“Ah yes. Of course. The famous Selene. Anchoress of Eridan.” He nodded thoughtfully. “I’ve read much of her teachings. Wise and devout—if a bit, shall we say… eccentric? Or rather, unconventional.”

He glanced back at me with a knowing smile.

And in that moment, I knew: he had read her. Not just about her. There was recognition in his tone—an ease, a fondness even. Perhaps he was someone I could trust. Or at least, someone I could speak to plainly.

“But I’m afraid,” he said, and then paused. We had reached a sealed metal door—indistinguishable from any of the others lining the corridor. “Ah. Here we are.” His tone lifted. “It’s always tricky to know which room is which around here. Please—come in. I’ve made tea. And that’s no small feat aboard this ship.”

The door slid open with a soft hiss. As Brother Wells stepped through, I caught a curious detail: his pupils expanded rapidly, adapting to the shift from the bright corridor to the dimmer lighting of the cabin. Far more than seemed natural. But before I could look closer, he had turned away, already heading toward a modest kitchenette at the far end of the room.

A compact teapot, transparent and thermal-sealed, sat resting on a folded gray-and-white striped towel. Wisps of fragrant steam curled from its spout—warm, spiced, and utterly inviting. It was one of those tourist-ship models meant for brewing with rationed water and mineral packets, but it smelled miraculous.

Wells opened a cupboard and unlatched two metal-secured cups—clearly the only ones aboard—then placed them on the kitchenette surface beside the pot.

“Oh, one more thing I meant to ask earlier,” he said, reaching for the pot. “Why were you hiding on the ship?”

He didn’t press the question with force. Instead, he lifted the teapot with a slow, careful grace and poured two cups, handing one to me and gesturing to a small table tucked into the corner. I sat down, grateful beyond words.

He followed, setting down his own cup along with a small tray: a compact, rectangular block of dried fruit and compressed starch—ration cake, or something meant to resemble it. Not much, but I had never seen anything so welcome.

“Please,” he said. “Sit. I almost never have guests.”

(I’m fairly certain that was a joke. There were, after all, no other humans aboard the ship.)

“The machines,” I said quietly.

Wells raised an eyebrow, then let out a short, surprised laugh. “You can’t be serious.”

“They’re security machines,” I insisted. “They can detect changes in temperature, breathing, even heartbeats. There’s no telling how they’d respond if they found me.”

He shook his head, still amused. “I don’t know where you heard that, but I assure you—they can’t do any of those things. They’re glorified maintenance computers. At best.”

and locked from the inside.

I didn’t know what to say. Could it be true? Had I never been in danger at all?

“After tea,” he said, “I’ll show you. There’s nothing to worry about with the machines onboard. But for now, let’s leave all that aside. I’d love to hear more about your journey—your plans once we arrive. But there’s no hurry.”

He took a long sip of tea, then set his cup down gently. “You got here just in time. After we finish, we can pray the Vespers.”

I had been bracing for punishment so long that I forgot how to recognize mercy.

Perhaps that is what pilgrimage does—it prepares the heart for pain, but not always for hospitality. I had imagined arrest, confinement, judgment. But I was met instead with warmth. Tea. A name. A shared table.

I do not know yet if Brother Wells is trustworthy. But I know that something inside me shifted when I sat down. It wasn’t safety. Not quite. But it was something close to peace.

It is a strange thing to realize: the fear I carried for weeks might have been of my own making.

I took a bite of the ration cake.

It was dry, dense, and faintly sweet—more compressed survival block than dessert—but I nearly wept at the taste of it. The warmth of the tea, the simple act of sitting at a table, of being offered something without demand or suspicion… It undid something in me.

For weeks I had eaten in the dark, crouched in vents, counting each crumb. I had rationed not just food, but breath, thought, voice. To sit here now—visible, unrestrained, with a cup in my hands and someone across the table—it felt almost unreal.

I watched Brother Wells sip his tea, his expression serene. He asked no questions. He did not press. His calmness only deepened my unease, but in a new way—not from fear, but from unfamiliarity. I had prepared for opposition, not kindness.

What do you do when no one stops you from being a pilgrim?

I drank slowly, trying to stay present in the warmth before it slipped away.

I had not prayed since the vision.

Not truly. I had whispered fragments—lines remembered from canticles, half-formed questions—but nothing with shape or offering. Now, with my stomach full and my hands warm, I felt that absence more sharply than before.

It was easier to pray when I was hiding. When the world felt dangerous, and every silence felt like waiting for judgment.

But here, in this quiet room, met not with suspicion but with tea and welcome… I didn’t know what to say.

I had thought hunger would lead me to holiness.

But maybe holiness was already seated across from me, asking nothing in return.

Brother Wells finished his tea, setting the cup down with careful deliberation. He gave me a moment longer, as though he could sense that I wasn’t yet ready to speak.

Then, quietly: “Shall we?”

5

He stood, smoothing the wrinkles from his robe with a kind of practiced grace, and gestured toward a small alcove behind the kitchenette. It wasn’t much—just a blank wall with a mounted screen and a shelf where a prayer book and a folding icon panel had been arranged. A flame-colored cloth had been pinned behind it, likely torn from a ration wrapper or an old uniform. But somehow, it felt like a sanctuary.

The lights dimmed slightly as we approached. I wondered if that was intentional, or if the ship simply recognized the time.

“We pray according to the Old Orbit,” Wells said gently. “Even here, even now.”[7]

Here Wells referred to the original Earth-based orbital calendar used for liturgical timekeeping before the standardization of the Interplanetary Ecclesiastical Clock (IEC) in the late 38th century. It was based on the Earth's rotation and lunar cycles, including canonical hours rooted in solar day patterns—Matins, Lauds, Vespers, Compline, etc.—tied to terrestrial time.

To pray “according to the Old Orbit” is to align oneself with the rhythms of Earth, regardless of distance. It became a spiritual gesture of fidelity for off-world clergy and anchorites—a way of keeping time with the saints of the past, even when light-years away. Many viewed it as an act of humility and remembrance: to acknowledge one's origins, even while dwelling in the unknown.

He tapped the screen, and the familiar antiphon appeared in soft white text. The words glowed like they were being spoken already.

He didn't ask if I knew the responses.

He simply began.

I did not know the hour.

I had not known the hour in weeks. But somehow, as he stood before the shrine and spoke of the Old Orbit, I felt the time settle around us. As if the prayer had begun before we spoke it. As if the stars themselves had waited.

I was not ready to pray. But I stood anyway.

Faith begins with the motion of the body

before the mind dares to follow.

Sometimes the act of rising is itself a kind of belief.

***

Author's Note:

Vespers of the Exile (According to the Old Orbit)

For use on long transits, feast eves, or within the silent hours between worlds.

Opening

Officiant:

Let our prayers rise like vapor through the dark,

For night surrounds us, and we are far from home.

All:

Yet You are present in the stillness,

And Your word is light upon unseen paths.

Psalm of the Wandering Saints

You who walked in dry places,

Who lit candles in caves,

And charted stars not for glory, but for grace—

You whose names are written in fractured time,

Teach us to wait, to watch,

To kneel in motion and speak in silence.

You who slept aboard empty ships,

Whose altars were wires and dust,

Let our hands remember holiness

Even when no one sees.

Responsory

Officiant:

The heavens declare the memory of Your name.

All:

And the void does not unmake it.

Officiant:

Though the earth is distant and the calendar unmoored,

All:

Still we mark the hour, and call it Yours.

Canticle of Selene (optional)[8]

We are stitched to the threshold,

Not by certainty, but by call.

We eat what we are given,

We speak what we are shown.

We write with borrowed light.

some must pass through us unspoken.

All:

Blessed is the one who watches without end,

And does not turn back from the unmarked road.

Closing Prayer

Guide us through the silence, O Anchor of the stars.

Let our rest be holy, and our waking just.

Guard the thresholds we do not yet see,

And draw us nearer to the center of Your will.

All:

Amen

***

I did not know the hour.

we pass through it before we know.

I thought I would feel ready by now.

But readiness is not a flame you carry—it's a wind that sometimes catches the edge of your robe and lifts it without warning.

I have eaten. I have prayed. I have spoken my name aloud to someone else. These things are small. But they are more than I had when I boarded this ship.

Soon, we will descend. I will walk where she walked. I will see for myself what the silence has preserved—or destroyed.

If Selene is dead, I will bury her memory with care. If she lives, I will not leave until I have spoken her name.

And if I find only echoes, then let them be holy ones.

***

"O God, come to our aid." "O Lord, make haste to help us."

***

Chapter Four: The Dust Remembers

“There are places so silent, even memory echoes there.”

—from the Collected Sayings of Anchorite Jorin, c. 3912

Before the ground receives you, it waits.

No matter how many maps you’ve studied, no matter how many names you’ve whispered into the dark—when you arrive at a place like this, you are not a pilgrim. You are an interruption. A breath drawn too sharply in a room meant for prayer.

I do not expect to be welcomed. I expect only to walk gently, to listen carefully, and to disturb as little as I can.

If she is here, may she forgive my footsteps.

If she is gone, may she still hear them.

1

We began our descent just before the ship's internal clocks marked the first hour of rest.

I felt the shift before I saw it—an almost imperceptible tremor in the hull, a change in the sound of the air around us. The engines adjusted with a soft groan, and the stars outside began to tilt. Gravity—real gravity—returned in slow gradients.

Brother Wells said nothing. He simply nodded toward the nearest viewport and returned to his quiet preparations.

I stood at the window and watched the world of Eridan come into view.

It was not as I had imagined it. There were no glowing domes or silver monastic spires. Just a rust-colored surface, veined with deep ridges and scattered with patches of pale lichen. From above, it looked almost wounded—cracked and raw, as though still healing from some ancient burn.

But there, near the equatorial crest, I saw the remnants of the monastery. A ring of low stone structures barely visible from this height. One tower still stood. The rest had collapsed inward, like breath drawn in and never released.

It was quiet. No signal beacons, no transmissions, no visible movement. And yet, as we approached, I felt something reach out to me—not in words, but in weight. Like a hand on the shoulder. Like a name spoken just behind my ear.

2

When we arrived, we began on foot, heading toward the mountain that rose to the north—the place where, according to surviving records, the monastery once stood.

The mountain was unmistakable. It dominated the otherwise low, fractured landscape, a massive, jagged presence that cut upward through the gray-brown terrain like the spine of something ancient and buried. There were no roads, no markers. Just dust, stone, and silence.

The only signs of life were the strange fungi—pale, columnar, and faintly translucent—that dotted the ground in clusters. Scholars had documented them during earlier expeditions.[9] It was said that the monks of Eridan had cultivated them, not for food, but as building material.[10] Their structure calcified over time, hardening into something between coral and stone. The monastery, or what remained of it, had been shaped from this living architecture.

There were no trees. No wind. Only the distant curve of the horizon and the quiet sound of our own footsteps on ancient ground.

We arrived at night.

Fortunately, I had studied Eridani maps well—along with Selene’s and Saint Barlowe’s writings on the constellations from the Eridani perspective—so it did not take me long to find my bearings.

The stars here were unfamiliar but not unkind.

They turned differently above this world, like a prayer written in reverse.

We set foot on the valley floor on what, by Earth reckoning, would have been the 25th of July. I took it as a sign. It was the Feast of Saint James the Pilgrim—a fitting day for such a beginning.

So I knelt in the dust and said a prayer.

***

Protect me today in all my travels along the road’s way.

Give me a sign if danger draws near, that I may pause while the path is still clear.

Stand at my window when the vision is blurred, and guide me through what cannot be heard.

Carry me onward to my destined place—

as once you carried Christ in your close embrace.

Amen.[11]

***

I stood and hurried to catch up to Brother Wells, who had already begun walking ahead, leading the way through the barren Eridani valley. He had offered to accompany me as far as he could, but his duties required him to return to the ship. He promised he would meet me again in a few days—and assured me, with what I believed was genuine kindness, that they would not depart without me.

“Even here,” he said, “no one is abandoned.”

3

After several days of walking—only stopping when rest became absolutely necessary—Brother Wells slowed and pointed ahead.

"There,” he said quietly, “just beyond those ridges. The monastery is built into the lower cliffs of that mountain range. You can just make it out.”

I squinted through the dust-haze and saw what might have once been walls or spires—partially collapsed, half-swallowed by stone and time.

“It’s customary,” he added, “to say a prayer when it first comes into view.”

So, that is what we did.

Wells stood beside me a moment longer, then turned.

“This is as far as I can go. I must return to the ship. You’ll have to travel the rest alone—but don’t worry.

The Lord watches the pilgrim.

He walks beside you even in places where the Church cannot.”

He paused, then reached into his cloak and pulled out a small memory chip. He placed it gently in my hand.

“I believe this is the collection you were after when we first met,” he said. “The ship’s archives. The material isn’t accessible by standard machines—only a functioning SCRIBE can read it. If one still dwells at the monastery, you’ll need this.”[12]

I looked down at the tiny object resting in my palm. Smooth. Unmarked. Heavier than it should have been.

“Thank you,” I said, but the words felt insufficient.

Wells only smiled. “You’ve come this far. That means something.”

He turned and left without ceremony.

And I stood alone again, as I had so many times before. But something had changed. I was not the same pilgrim who had hidden in a vent, trembling with hunger and fear.

He gave me no map. Only the mountain. Only the silence. Only the chip.

But this is the way of the faithful. We are given just enough—not comfort, but continuity. Not certainty, but one more step.

I do not know what waits for me at the monastery. But I know who sent me forward.

And I know that is enough.

4

It did not take long to understand what earlier researchers meant when they described Eridan in terms of barrenness, desolation, and solitude.

After crossing the central valley, the terrain flattened even further—eerily so. The surface stretched outward in near-perfect uniformity, gray and unbroken but for the jagged scatter of dark rocks, as if the planet itself had exhaled its last breath and never drawn another.

There was no variation. No shelter. No sound.

I walked for hours—though I could no longer trust my sense of time—and developed several blisters beneath the soles of my boots. The chill of the windless dusk began to press into my bones when I finally came upon what I first mistook for a rise, but soon realized was a depression in the earth.

Not a cave, exactly. More like a pit—low and open to the sky, but shielded enough to break the night’s cold. It would have to serve as shelter until morning.

The foot of the mountain lay perhaps twenty miles ahead. I could see it now only as a shadow against the horizon. If the weather held—and if Christ in His mercy willed it—I would reach it tomorrow.

Tomorrow.

they arrive ready to be undone.

Tomorrow I will have my answers.

About the monastery. About the SCRIBES.

About the one they call the final anchorite—

the one I have followed in silence for so long.

Selene.

I do not feel holy tonight.

I am cold. I am sore. I am far from anything resembling a shrine.

But I have come this far, and I will not turn back.

This planet does not welcome pilgrims. It offers no trail markers, no water, no shelter—only stone and stars, and the slow ache of feet pressed to ground that does not yield.

Yet I believe this, still:

There is grace in motion.

There is prayer in walking.

And if she is there—

I will find her.

5

I am writing this by the faint light of my camp lamp, which flickers more with each passing hour. I do not know how long its charge will last.

The cold here is not cruel. It is ancient. It does not seek to harm—it simply refuses to notice me. As though the land itself no longer remembers what it means to welcome breath and heat.

I have recited none of the expected prayers tonight. Instead, I have only listened. And I have heard nothing. No wind. No creatures. Not even the sound of my own breath when I try to listen for it.

But this silence is not empty.

It is full. Heavy. Attentive.

I do not know if I will sleep. I do not know what I hope to find tomorrow. I only know that I am closer now than I have ever been.

6

I do not remember falling asleep. But I remember opening my eyes.

There was no pit, no shelter, no stars. Only blackness—alive, not empty. It rippled like cloth pulled gently in water. A light appeared before me, diffused and soft, like the gleam on a waxed icon.

Then I saw her.

Not clearly. Not like before. This time she was cloaked—hooded and veiled in layers of fabric that shimmered like the inner surface of a mollusk shell. No face. Only the sense of presence. Only a feeling that she was watching me, and that I had come too soon.

She raised a hand—not in greeting, but in warning. Slowly, deliberately.

A circle of symbols glowed at her feet—neither letters nor numbers, but something deeper.[13] Something pre-verbal. I could not read them, but I understood their gravity.

Then, a whisper—not from her, but from the space around her:

What does memory preserve—truth, or only the wound?

“Do not enter lightly. The house of memory does not forget its visitors.”

I awoke with a jolt. The lamp had gone out. The stars were still overhead.

And I could still feel the shape of her presence on my skin.

The sky was pale when I rose. Not bright, but less dark.

I did not dream again, but I felt the shape of the vision lingering behind my eyes—like an afterimage burned into the soul. I do not know if it was a message, or only my mind reshaping silence into a form I could bear. I do not know if it matters.

Some truths cannot be proven. But they still arrive, like dawn—subtle, slow, and unable to be argued with.

I have said no formal prayers this morning.

I only stood in the cold, and whispered: “I am still coming.”

And if the mountain heard me, it did not respond.

But it did not stop me either.

***

[1] Authorship has been traditionally attributed to Benedicto Vox, who discovered the journals among a collection of notebooks, hardrives, and memory chips. However, Vox would certainly have died before 4476, the accepted date of the discovery. It is unclear who completed Vox's work or assisted with the discovery and recovery of these lost texts. Furthermore, details, such as chapter titles, were attributed after the fact, by later editors. Lina's original writing contain no headers or section titles. ↩

[2] Antipope Victor IV and V are excluded from the sequence of Pope Victors, thus Genesio Borghese, chose the name Victor IV and served as Pope from 4393 until 4408. ↩

[3] The STS (Space Transportation System) Zenith Sanctus was one of the last sanctioned vessels used for ecclesiastical deployment to Eridan. According to Transit Archive Records, it was scheduled for decommissioning shortly after its 4400 voyage ↩

[4] Frequent contradictions in the recorded accounts have led to confusion over whether or not the ship was unmanned. The author here is mistaken and therefore his note is of little use. Previous editions of this text state that no humans were onboard. However, there absolutely were humans on-board during Lina's trip, but they played little role in navigation or operation—possibly explaining her lack of reference to them. Regarding food and hygiene. She mostly likely simply stole food and supplies from the ship's stock as needed without the crew noticing. Of course, it is worth noting that an increasing number of scholars now regard Lina's writings as fictional (or at least semi-fictionalized) rather than strictly autobiographical. ↩

[5] The contents of the memory chip Lina carried have never been conclusively identified. Theologian Orren Jax of the Mare Acidalium Collegium argued in his treatise Fragments in Exile (4521) that the chip likely contained raw hex-encoded excerpts from Selene's disputed Post-Revelation Notebooks, smuggled from a sealed vault beneath Saint Selene Abbey. Others, like the archival theorist Mera Solas, proposed that the chip held only blank storage space and a set of subversive indexing protocols—custom tools for navigating and extracting forbidden texts from shipboard archives.

One minority tradition, upheld in the East Noachis School, claims that the chip was actually devotional: an object of ritual memory modeled on the pre-Schism Cortana Devices, which were once carried by pilgrims who had vowed to copy and transmit sacred texts by hand if systems failed. According to this view, the act of touching the chip mid-journey was not just preparatory, but sacramental.

Regardless of its content, most commentators agree that Lina intended to use the chip in the archive room to retrieve or preserve any surviving Eridani manuscripts—especially those relating to the SCRIBES, or to Selene’s final years. That the chip is never mentioned again has led to further speculation: either its mission was fulfilled off-page, or its erasure was deliberate.

↩

[6] It is likely that many of the volumes stored here were among those recovered in the 4476 trove, later cataloged as part of the Vox Fragment Collection. The presence of both digital media and physically preserved texts suggests that this room served not only as an access terminal but as a holding archive for materials deemed too fragile—or too sensitive—for ordinary ecclesiastical circulation. ↩

[7] The “Old Orbit” refers to the pre-Schism liturgical calendar maintained according to Earth's rotational time and canonical prayer hours. Though outdated by most interplanetary standards, it is still followed by some religious orders as a sign of fidelity to terrestrial tradition and continuity with the early Church. ↩

[8] The Canticle of Selene is a devotional fragment of uncertain origin, believed to be compiled from various entries in Selene's Revelations of a Scribal Faith and her final encoded writings. Though never officially canonized, it has been widely adopted in Eridani liturgy, especially among anchoritic and itinerant orders. Scholars debate whether Selene authored it in full or whether later SCRIBES collated the verses posthumously, interpreting her marginal notes as liturgical. The phrase “we write with borrowed light” is frequently cited in threshold prayers and exile masses. ↩

[9] The calcifying fungi of Eridan were first catalogued by Saint Barlowe in the 37th century. He noted their unique biostructural capacity to harden over time and fuse into stable, load-bearing formations. Modern myco-ecclesial studies suggest these organisms were deliberately cultivated by Eridani monks as part of a monastic philosophy that sought to merge living growth with architectural permanence. ↩

[10] Controversy remains over whether the fungi were genetically altered by the early SCRIBES or adapted naturally through proximity to the monastery’s sacred practices. The “Fungal Rule,” an informal name given to a fragment of unknown origin found in the Vox Fragments, claims: “We do not build with stone, but with the patience of spores." ↩

[11] The prayer Lina recites is a variation of the Prayer to Saint Christopher, long associated with safe travel and pilgrimage. Though Saint James is more commonly invoked on July 25th in liturgical calendars, some early Interplanetary missals preserved the joint commemoration of both saints on this date. Saint Christopher’s legacy endured in devotional practice, especially among spacefarers who adopted him as an unofficial patron of interstellar transit. ↩

[12] The chip given to Lina is believed to contain select files from the Eridani Archive Segment of the SCRIBAL ship index, accessible only through decrypted ecclesiastical SCRIPTOR protocols. These data packets were encoded using pre-Schism liturgical codices and nonstandard linguistic indexing—rendering them unreadable by standard civilian systems. Some scholars argue that these chips were less storage devices than ritual keys: access dependent not on code, but on presence—on being near a functioning SCRIBE whose cognition was shaped by sacred heuristic matrices. ↩

[13] The “circle of symbols” described in Lina’s vision has been the subject of considerable debate among exegetes of the Vox Fragment Collection. While no known script directly matches the described forms, several scholars—most notably Idris Cora and Elyra Jhelt—have compared them to early Eridani cipher-runes used in SCRIBAL system-binding rituals. Others have suggested the symbols reflect a theological syntax rather than a linguistic one, designed to be apprehended intuitively rather than decoded. In some apophatic interpretations, the circle is understood not as a message to be read, but as a threshold—one that separates memory from manifestation. ↩